As much art as science

From November to January, we had an artist-in-residence here at MARE-Madeira, working closely with our Marine Technology & AI team (Wave Labs). If you came to our MAD-Deep Symposium, you may have seen (and heard!) the artwork Victoria Evans made with our researchers during her residency – The Whale Whisperer.

An historic partnership

In the past, artists worked closely with biologists and ecologists. Illustrators, and subsequently photographers, were key members of many historic scientific expeditions. Like Conrad Martens illustrating the species Charles Darwin described on the voyage of the HMS Beagle in 1831; or John James Wild, the artist for the HMS Challenger expedition in 1872; or Herbert Ponting photographing wildlife alongside scientists on Robert Scott’s last Antarctic expedition in 1910. Now that photography is commonplace however, artists are rarely considered essential components of (regular) scientific work… But are we missing something by this technologically-aided divorce of art and science?

Castor oil plant, Conrad Martens (Sketchbook I, Voyage of the Beagle), Copyright Cambridge University Press, CC NC; HMS Challenger Papers, No.151, Copyright The University of Edinburgh, PAF.

Victoria Evans is a PhD student at the Edinburgh Art College, part of the University of Edinburgh. Thanks to funding from the Scottish Graduate School for Arts and Humanities, Victoria was also our first artist-in-residence here at MARE-Madeira. I caught up with Victoria after her residency to hear her thoughts on the experience, her views on what art and science can offer one another and how we (and other research institutions) can better embrace this age-old channel for showcasing the marvels of nature.

A different perspective

In our interview, Victoria was keen to move away from the notion that artists only represent or illustrate science. She suggests that a key role for artists within science is in asking questions (which are naturally going to be different from those of a scientist) and seeking explanations that are different from those a scientist might write in a science journal. “I think there’s a value for any profession in being forced to look at their work from a different perspective – it’s a luxury, maybe, but I think it can be very valuable.” She also explored the value of ‘holding that space of questioning open for longer,’ which has been described academically (see ‘Further reading’ below). As Victoria explained, “Art can have a very different definition of what is ‘useful’ than science does, and different timescales for finding ‘answers’ in our research. Of course, we’re all very driven and focused on productivity and efficiency and getting this published and that funded. But perhaps there’s something to be gained by someone pressing the pause button on our work. Just for a minute.”

Innate to art and artists is that constant, ever-evolving hunt for how best to connect with one’s audience. Artists are always thinking about how to convey a message in a way that resonates with others. In science, there’s a lot of pressure for us to do this better. There’s a frustration, really, in the wider community that science can be so elusive. No one wants to read a scientific journal, but as journal articles are the measure of success (and future funding) in science, they are naturally the focus for most scientists. As we try to find ways to communicate what we do in an accessible way, there’s surely much to learn from artists, for whom connection and communication is core to their discipline.

Victoria modifies this thought somewhat. “In my case, I’m less interested in sending a message and more interested in asking questions. I’m intensely curious, and I get really excited about the amazing research being done at places like MARE-Madeira. What I want to do is create something that, in some way, is a manifestation of that magic and wonder.”

Cultivating curiosity

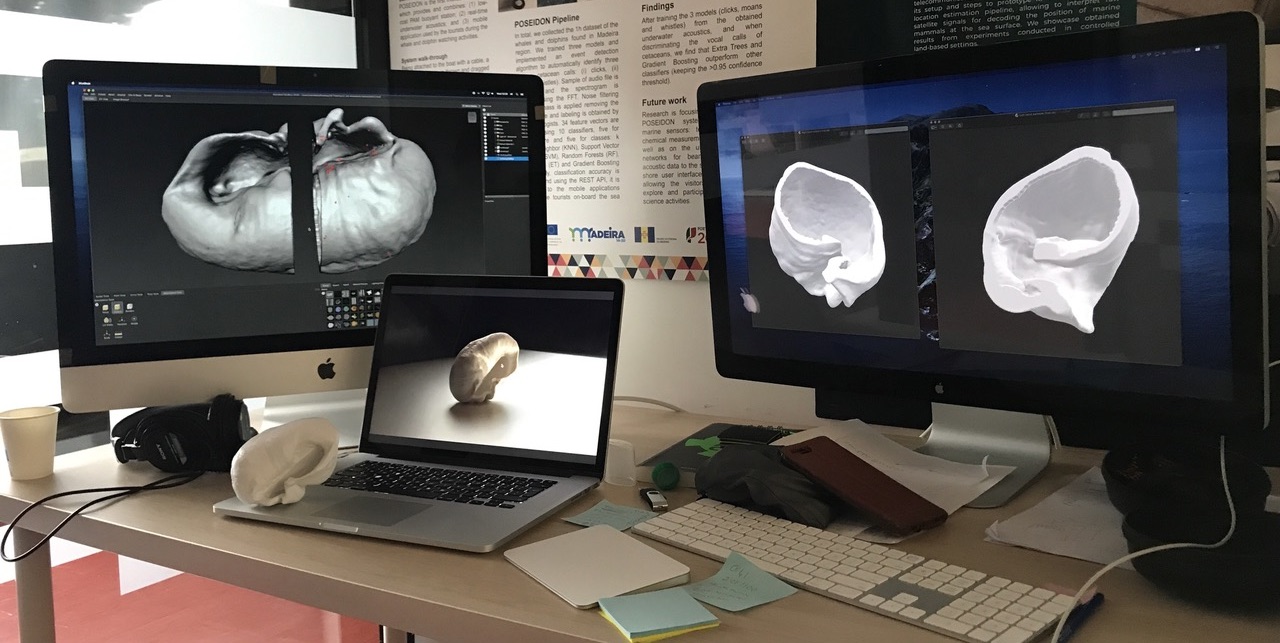

In other words, through her art, Victoria seeks to cultivate curiosity in others. And with ‘The Whale Whisperer,’ she certainly achieved it. For those who didn’t get a chance to see it at MAD-Deep, The Whale Whisperer is a 3D printed whale earbone, which you can hold up to your ear and listen to cetacean recordings. The art piece was inspired by Victoria’s fascination with how whales communicate underwater and the research she was able to do on the topic at MARE-Madeira.

“I had a lot of ideas in the early weeks at MARE-Madeira. I immersed myself in everything people gave me to read, talked to researchers and did a lot of online research.” (You can see the variety of early-stage ideas on Victoria’s blog) “So it was a case of finding the one idea that would enable a genuine collaboration between me and the marine technology team, that would relate to the research being done here, and that would be doable within the three-month time frame. Quite quickly, Marko and I decided that this was the one.”

And so began the process of designing an artwork that could make a connection between whale vocalizations in the water and a non-scientific audience on land. “We also wanted to promote a way of interacting with whales that is not intrusive or distressing to the animals, yet still feels personal and intimate.”

Using the anatomical shape of a whale earbone as the ‘vessel’ for this experience was a serendipitous bonus. “I did a lot of research about whale hearing, studying the anatomy and physics of it. They don’t have an external ear like we have; instead they have this shell-like bone inside their skull that soundwaves resonate with. I was just blown away by that idea and wanted to recreate it. I also really liked that the size of a blue whale’s earbone is something you can hold in your hand, highlighting the scale of these creatures. It was just a lovely kind of poetic thing. If people didn’t know, they might think they were listening to a shell. But when you tell them it’s a whale earbone, it’s kind of mad and suddenly really magical.”

Which was evident when The Whale Whisperer was put on display at the MAD-Deep Symposium. “The photographs look staged, but honestly, every person that picked it up and listened started smiling! I found that really lovely.”

That sense of wonder is probably because few people have had the opportunity to hear whale vocalizations before. “Some may have heard a humpback whale recording, as those were made quite famous in the sixties from a recording by Roger and Katherine Payne,” Victoria explained. “But most people have never heard a sperm whale click, and blue whales are almost outside our range of hearing, anyway. But with a slightly speeded-up or pitched-up recording, they get a glimpse of how these creatures talk to each other across miles and miles and miles of ocean.”

Which, on MARE-Madeira’s communication team, we obviously love. As soon as we find the funding for it, we’ll recreate The Whale Whisperer and have it at every MARE-Madeira stall from now on!

A true collaboration

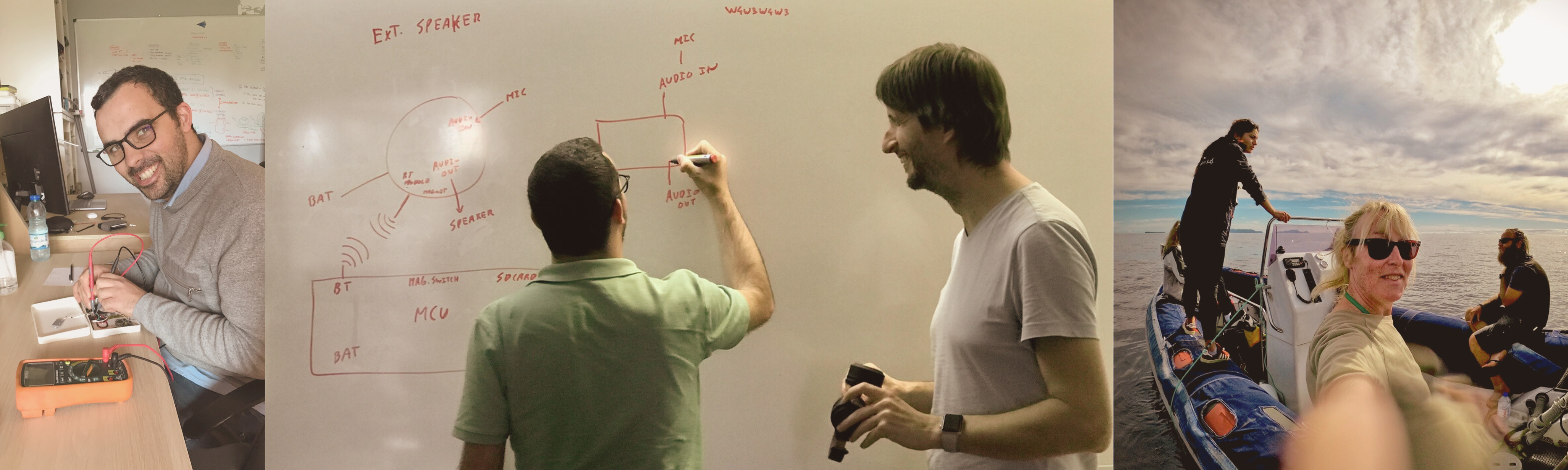

For Victoria, the greatest success was that The Whale Whisperer was a true collaboration. “Marko spent a lot of time mentoring me and João (Pestana) was brilliant in figuring loads of stuff out. We were back and forth constantly about how we were going to do it, how we could conceal the electronics, how it could be charged… I was super impressed and liked that it really became a genuine collaboration between Marko, João and myself, with input from Laura (Redaelli, on the marine megafauna team). We started to understand each other – they understood why certain things were important to me, and I understood some of the practicalities. And actually, it wasn’t so much them telling me what we couldn’t do, but more like, ‘We can do this!’ which I’d not even thought of! It was amazing. I think the collaboration was the real achievement.”

Victoria also celebrated how much she was able to learn. “I always knew I was interested in the materiality and physics of sound, but I wasn’t sure how I was going to get to grips with that knowledge, especially in the context of marine acoustics. Getting hands-on experience and working alongside Marko, João and Laura – well, I just don’t know how else I would have learned so much. Of course, you can read about something, but seeing it in action, having someone to ask, trying things out and actually working with people that know what they’re talking about is invaluable. It was really, really great.”

And last but not least, was the art itself. “I’m so chuffed! We actually made a piece that we could exhibit! I didn’t think we would finish in time. That’s something to celebrate, too.”

We were lucky to have Victoria, to help us share the ocean’s wonders with our community. And she deserves huge congratulations for jumping in the deep end, surrounding herself with scientists and engineers who haven’t hosted an artist before. It was a brave thing to do and we’re very glad the risk and uncertainty paid off! And with it, art once more proved its power to bring science to the general public in an inspiring, relatable way. So long as we prioritize time for it, we hope that art and science will continue to find a way back to each other and show that, together, our two disciplines are stronger than they are alone.

Want to give it a go?

For those artists considering a residency at a scientific institute, Victoria shares a few tips:

- Find a scientist who is enthusiastic to host you and willing to give you their time. That will set you up for success.

- Be prepared to explain the value you can bring to the institute and how you can help them reach their own goals.

- Be flexible. The way things are done in science are not the same as in humanities, obviously, so it’s important to adapt to new ways of working.

And for those institutes interested in hosting an artist-in-residence, we can recommend:

- Share the rational for the residency early on, to get as many scientists excited about the idea as possible. The more enthusiasm across the institute, the more willing people will be to find time to help, and the more it will set the artist up for success. Since artists-in-residence at research institutes are still a rather foreign concept, there’s likely some level of internal education to be done about the ‘whys’ and ‘hows’ before they arrive.

Further reading

Lehnmann, J., Cole, R.G., Stern, N.E. (2023). Novelty and Utility: How the Arts May Advance Question Creation in Contemporary Research. Leonardo, 56(5): 488-495. https://doi.org/10.1162/leon_a_02400