Dust Bowl of the Deep

In the late 19th century and early 20th century, the Great Plains of America were seen as a promised land of plenty, with endless space and resources for agriculture. The American government offered land to those who moved west and many grasped the opportunity. This land rush accelerated after World War I when wheat prices skyrocketed. Land under cultivation doubled, then tripled, then grew some more. At the same time, the combine harvester allowed for the harvesting of larger fields and tractor-pulled plows dug deeper into the soil to extract more and more nutrients. Planted wheat and corn spread like wildfire over the land and by 1930, hardly a blade of prairie grass remained.

What happened next has been described as the worst man-made ecological disaster in American history. Drought combined with high winds and man-made erosion led to ferocious, never-ending dust storms. Over the course of the 1930’s, these storms took the health, homes and livelihoods of millions of Americans. Many others perished from malnutrition or dust pneumonia.

This time period is now referred to as the Dust Bowl. And it is just one of many examples across human history in which we assume natural resources can be taken from their ecosystems without consequence.

“The irresistible promise of easy money and the heedless actions of thousands of farmers, encouraged by their governments, resulted in a collective tragedy that swept away the bread-basket of the nation.”

Ken Burns in The Dust Bowl, a PBS documentary

There are notable parallels between the deep sea today and the Great Plains of the 1920’s. We have technologies now that can access its resources, and we are promised wealth and prosperity if we take them. And just as growing crops on the Great Plains was meant to solve the agricultural needs of a growing nation, plowing the deep sea is meant to solve the climate crisis by providing us more metals to make batteries. Like the suitcase farmers who read of free money out on the Great Plains and rushed to till it, deep-sea mining companies are now springing up, ready to vacuum metallic nodules from the seabed as soon as governments say ‘Go’.

There are, however, two key differences between farming the Great Plains and mining the deep sea (beyond the obvious that one is underwater and at 500x the pressure of sea-level!). But instead of consoling us that ecological disaster is less likely in this instance, these differences should give us more cause to pause.

The first difference between farming the Great Plains and mining the deep sea is that the deep sea is a slowly-changing environment. Plants, animals and nutrient cycles on land reproduce, move and regenerate relatively quickly in comparison. Rewilding projects on land, for example, take a matter of a few years to make a noticeable difference and as little as ten to mirror their fully wild counterparts. In the deep sea, however, and likely because of the absence of light and its slow-moving currents, the ecosystem doesn’t easily adapt and recover. Various studies have been conducted to simulate deep-sea mining and the impacts on plant and animal life, and in these studies, very few species return to pre-mining levels, even after two decades (Jones, et al., 2017). One study in which a field of nodules was plowed by researchers in 1989 and revisited 26 years later demonstrated that not even microbial life fully recovered after so long a time (microbial life remained at least 30% below that of non-plowed areas) (Vonnahme, et al., 2020). These studies suggest that the damage we do to the deep sea may not be easily undone.

The second difference between farming land and mining the deep sea is knowledge. By the time of the Dust Bowl, mankind had been farming for approximately 15,000 years. The value of crop rotation and diversification had long been established; we knew the growth and reproduction cycles of plants; we knew of the nitrogen cycle; we knew of microbes in the soil and on roots. While that knowledge clearly wasn’t enough to avoid ecological disaster (we as humans are very good at selecting to observe only that knowledge that suits our mercenary ambitions), it was enough for the government and conservation societies to launch relatively effective mitigation efforts in its aftermath. In contrast, we know very little about the deep sea and are unprepared to ‘fix’ any damage we do. Given the challenges of access and chronic under-resourcing of marine research across history, few marine research institutes today have sufficient resources to study the deep sea. Those that do have only had a few decades to monitor and study this environment. Certainly, it’s a far cry from 15,000 years of land-based knowledge.

You may well wonder what the big deal is, though. For even if we don’t know much about the deep sea, does it really matter if we disturb so seemingly-empty, slow-to-change and distant a landscape? Would a dust bowl in the deep really bother anyone?

“When one tugs at a single thread in nature, he finds it attached to the rest of the world.”

John Muir, Naturalist

The little we do know about the deep sea shows it plays several vital functions in sustaining life on earth. For example, the deep sea is important in nutrient cycles that feed the rest of the ocean, including the fish we eat. It is important in carbon sequestration (estimates suggest the ocean absorbs one-third of the carbon dioxide we emit into the atmosphere by burning fossil fuels, most of which is stored in sediment on the sea floor). The deep sea is also important in the detoxification of chemicals that escape from the earth’s crust (chemosynthetic microbes on the sea floor and on deep-sea vents convert the methane and hydrogen sulfide that seeps up into non-toxic sulfur, sugars and carbon dioxide). Disrupting any of these processes could have a significant impact on life in the ocean, on atmospheric carbon and, consequently, on us. How tragically ironic would it be if we mined the sea floor to make more batteries to ‘solve’ the climate crisis and ended up making it worse by kick-starting a process that returned some of the billions of tonnes of carbon in deep-sea sediments back into the atmosphere?

At MARE-Madeira, we are not experts in the deep sea (yet!). We don’t know the effect that deep-sea mining will have on the ocean. What we want to stress here, though, is that no-one really does. We (as a global community) haven’t studied the deep sea enough to know the long-term impacts we will have by extracting resources, reducing habitats, disturbing life and churning up large swathes of sediment from the deep.

What we do know is that the ocean is already under significant distress from overfishing, the hunting and inadvertent killing of apex predators, chemical and plastic pollution, coastal development and the destruction of carbon-fixating, oxygen-producing and water-filtering coastal habitats, the spread of invasive species, acidification from rising carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere, rising water temperatures, and the changing of salinity from glacier melt that affects the ocean’s cycling of oxygen, nutrients and global temperature regulation. With this and more, we already have enough messes in the ocean to clean up – and so far, we’re proving terrible at doing so. Oil remains from our spills for decades, major fishery stocks and whale populations remain far below pre-industrial fishing and pre-whaling levels, micro- and macro-plastics have infiltrated all life and corners of the ocean, the on-going spread of non-indigenous species continues to damage biodiversity, and ocean currents are already slowing from rising sea temperatures. What we need now is a healthy ocean, not further exploitation. What we need now is more research, not nodules.

More research, not nodules

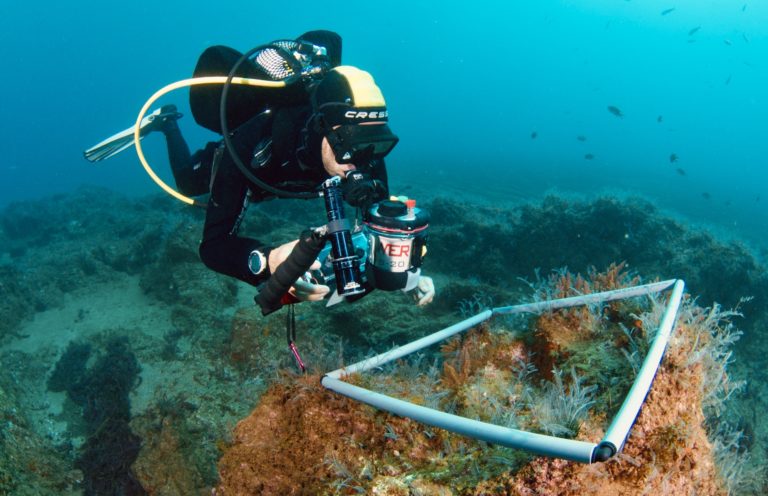

We are in the early stages of developing a deep-sea research program at MARE-Madeira. With our island’s easy access to the deep sea, mild climate and calm seas, we can study this environment more efficiently than many other locations around the world. As a global community facing global threats of climate change, warming oceans and dwindling biodiversity, it is to our benefit to join together and study the deep sea where it is quickest and cheapest to do so.

If you would like to support deep-sea research or partner with us, please reach out. We are a small team and growing quickly, but we will always find the time to speak with those who can help us reach our goals. Together, we believe we have the best chance to address our ocean’s (and our planet’s) greatest threats. Together, we have the best chance to learn about Earth’s final frontier and the role it plays in sustaining life on earth. Together, we have the best chance to avoid the Dust Bowl of the Deep.

Learn more

About the ocean, the deep sea and deep-sea mining:

Roberts, Callum. (2013). Ocean of life: how our seas are changing. London: Penguin.

Scales, Helen. (2021). The brilliant abyss: exploring the majestic hidden life of the deep ocean and the looming threat that imperils it. First edition. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press.

Amon, Diva. A Rush to Mine the Deep Sea Is Underway. It Must Be Stopped. New York Times, March 15, 2023. (Written by a fellow Edinburgh Ocean Leader)

About the effects of mining on deep-sea habitats:

Vonnahme, T.R. et al., Effects of a deep-sea mining experiment on seafloor microbial communities and functions after 26 years.Sci. Adv.6, eaaz5922(2020).DOI:10.1126/sciadv.aaz5922

Jones D.O.B., Kaiser S., Sweetman A.K., Smith C.R., Menot L., Vink A., et al. (2017) Biological responses to disturbance from simulated deep-sea polymetallic nodule mining. PLoS ONE 12(2): e0171750. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0171750

About the Dust Bowl:

Dust Bowl – A 1950s Documentary, McGraw-Hill

The Dust Bowl (2012) Ken Burns, PBS

About rewilding on land:

Tree, Isabella. (2019). Wilding. London, England: Picador.

Photo credits: “Fleeing a dust storm,” Farmer Arthur Coble and sons walking in the face of a dust storm, Cimmaron County, Oklahoma. Arthur Rothstein, photographer, April, 1936. (Library of Congress); Black Sunday April 14, 1935 (both accessed from the US Department of Agriculture). Invertebrates on Canyon Wall: NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Deep Connections 2019. ROV around Madeira: Nuno Vasco Rodrigues, Conservation Photography (nunovascorodrigues.com).