Jellies! and the dangers of an unregulated industry

If you’ve ever been stung by a jellyfish, you may not feel particularly inclined to protecting this ocean critter. And if someone told you that populations of jellyfish are at risk of depletion, you may well think, “Good riddance.” But if, on the other hand, you tuned into the JellyWeb Cruise*, then you’ll know that jellyfish play a critical role in ocean food webs. Jellyfish are easily-digested food for all sorts of fish, turtles and seabirds. If there weren’t jellyfish, there would be fewer unpleasant stings on the beach — yes. But there would also be much less food for huge swathes of higher-order ocean life. (Chi et al, 2021)

We’re here to tell you that jellyfish populations are indeed at risk of depletion. The reason they’re at risk of depletion is not that they’re vulnerable species at present – but rather because they’re entirely unregulated.

Fun fact: jellyfish have been around for over 500 million years, making them older than dinosaurs!

Photo credit: Susi Schäfer

Jellyfish are increasingly of interest to industry for their nutritional, cosmetic and agricultural applications and medicinal properties (Edelist et al, 2021). Through our work in the GoJelly project,** we collaborated on sustainable use cases for jellyfish; in particular, the use of jellyfish mucus as a microplastics filter. In these myriad ways, jellyfish may provide sustainable solutions to some of our pressing environmental and health challenges. Combined with the observation that climate change and ecosystem imbalances are causing jellyfish blooms (warmer waters and our overfishing of jellyfish predators is causing population explosions in some areas), there’s a potential to use jellyfish in a sustainable way while also addressing human-induced ecosystem imbalances.

As a society, however, we’ve never been good at ‘just taking a little’. Consider the beaver hat fad that caused near-extinction of beavers in Europe in the 17th century, or the mountains of oysters dredged up from the once-blue Chesapeake Bay (150 years later, the still-brown bay has yet to recover its valuable filter-feeders). As soon as we see something of value that is unregulated, we take all of it that we can find. Jellyfish are no exception. In some waters, and despite the aforementioned blooms, jellyfish stocks are already depleted to an extent that only aquaculture remains as a viable harvesting solution.

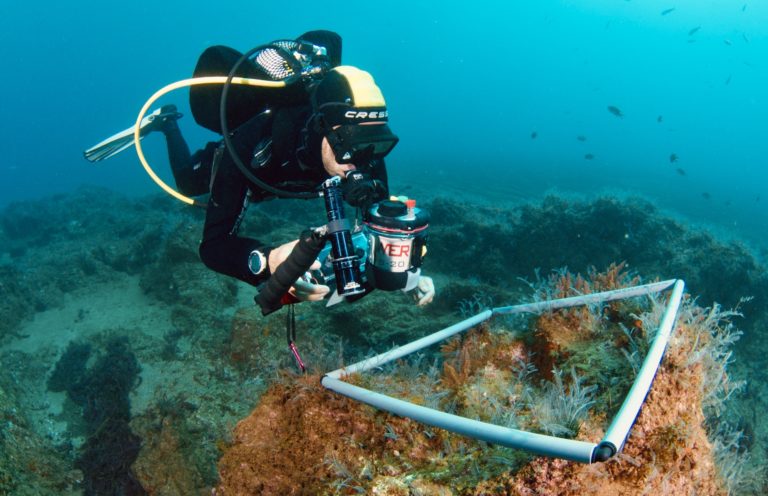

Researching gelatinous zooplankton around Madeira on the JellyWeb Cruise 2024. Photo credit: Florian Lüskow

What can we do to prevent jellyfish depletion in other places? The answer (until we change innate human behavior and the incentives within capitalism for overexploitation of resources, at least) is regulation.

Just as it does for fish, the regulation of jellyfish will mean gathering more data about jellyfish populations and bycatch from industry players — data that can be used to make informed policy decisions on harvesting limits and precautions. This data, alongside scientific studies, will be essential for monitoring population levels and ensuring a sustainable industry can be born. Consider: if no one knows how large jellyfish populations are, nor how regularly they’re being caught in bycatch, nor how many are being harvested, then no one knows how many are left — until they’re all gone.

Recognizing both the potential of jellyfish and the threat they’re facing as an unregulated animal product, our GoJelly project partners have created a petition. This petition is gathering scientific and public support for the regulation of jellyfish harvesting — just as fish and other ocean life used for human consumption and products are regulated. Only when governments and regulating bodies create guidelines, reporting frameworks and use limits for jellyfish can this nascent industry have a chance of becoming sustainable.

If you’d like to ensure jellyfish are used sustainably, then do consider signing the petition. And thank you for taking the time to learn more about jellyfish!

*The pelagic and deep-sea research expedition around Madeira this February, which focused on gelatinous zooplankton and their role in oceanic food webs.

**GoJelly was a European Commission-funded project across 16 partners in 9 countries with an aim to identify sustainable use-cases for jellyfish and inform policymakers and wider stakeholders on jellyfish use. https://web.archive.org/web/20230215134243/https://gojelly.eu/

Further reading

Chi, X., Dierking, J., Hoving, H.-J., Lüskow, F., Denda, A., Christiansen, B., Sommer, U., Hansen, T. and Javidpour, J. (2021), Tackling the jelly web: Trophic ecology of gelatinous zooplankton in oceanic food webs of the eastern tropical Atlantic assessed by stable isotope analysis. Limnol Oceanogr, 66: 289-305. https://doi.org/10.1002/lno.11605

Edelist, D., Angel, D.L., Canning-Clode, J., Gueroun, S.K.M., Aberle, N., Javidpour, J., Andrade, C. (2021), Jellyfishing in Europe: Current Status, Knowledge Gaps, and Future Directions towards a Sustainable Practice. Sustainability; 13(22):12445. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212445